Virus definition

To put it simply, viruses are infectious pathogens that require a living body cell to reproduce, meaning they are themselves parasites. The cells that serve as hosts can come from humans, animals, plants and even bacteria. But not every type of virus is able to infect every one of these organisms. Viruses can also exist outside of a host cell. They are then referred to as virions or extracellular virus particles. But viruses cannot reproduce in this way.

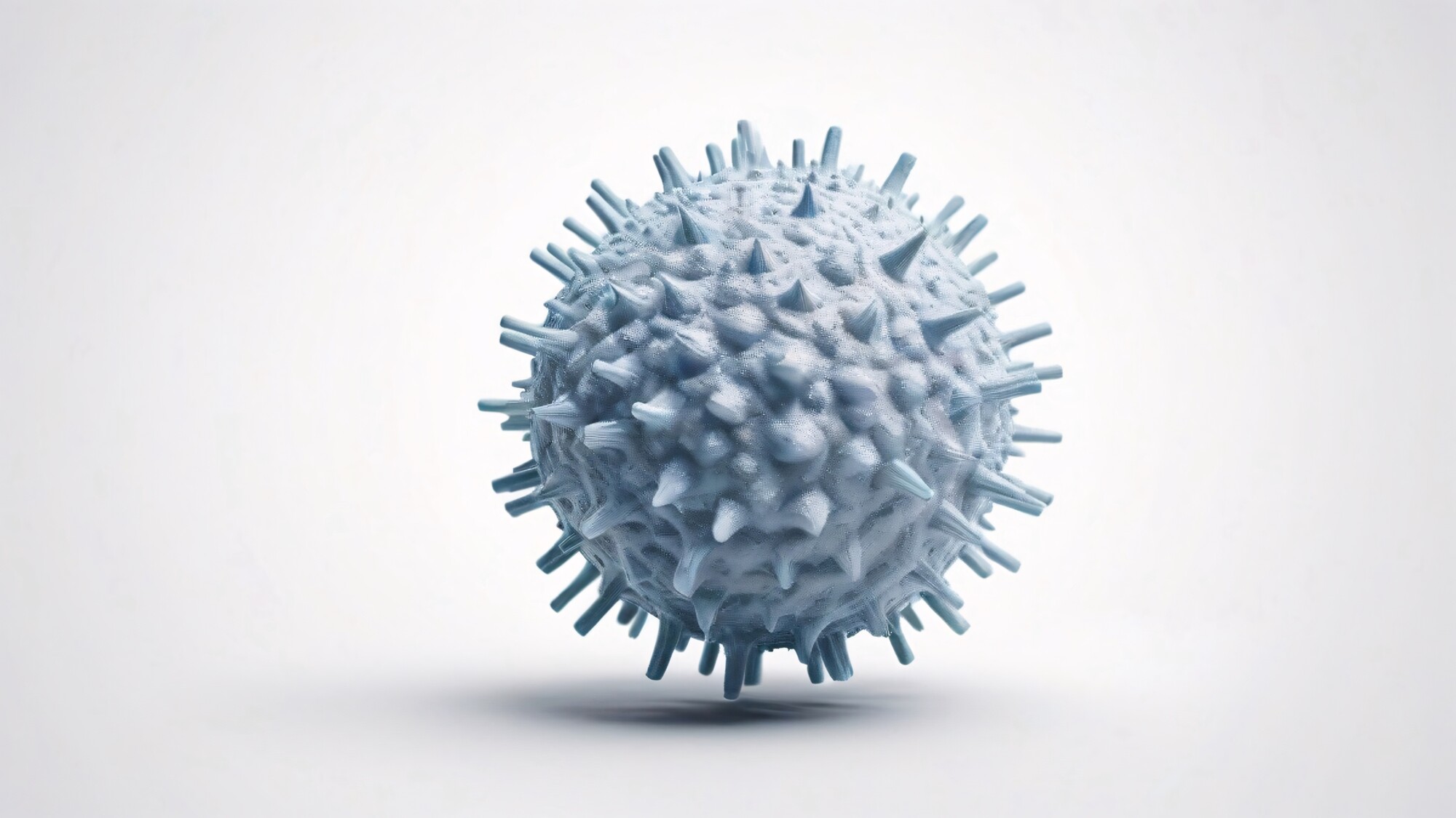

What exactly is a virus?

Viruses cannot be considered independent living organisms because they do not have their own metabolism. They consist mainly of genetic material (DNA/double strand, or RNA/single strand copy) and a protein shell (capsid).

Viruses depend on host cells because they lack important, essential components for reproduction. They do not have their own system for protein synthesis. However, the production of proteins is essential for the reproduction and thus the long-term survival of a virus strain.

The structure of viruses

In addition to the differences in the genetic material (DNA or RNA), other components of viruses can also be different. For example, not every virus has an outer viral envelope.

However, all viruses have the capsid in common, a protein shell that surrounds and protects the viral genetic material. As can be seen from the illustration above, the exact configuration of the viral capsid is different. Some viruses also have a lipid membrane that they take over from the host cell and that surrounds the capsid. On the outer shell of the virus there are spikes (glycoproteins), surface proteins that are responsible for binding to the receptors of the host cell and thus enable entry into the cell.

Life cycle of a virus

Viruses are transmitted from one organism to the next. This can happen from person to person, from animal to animal or sometimes from animal to person. In principle, transmission is possible via saliva exchange, via stool particles that have entered the mouth, via blood, semen, vaginal secretions or as droplet infection via the air we breathe, as well as via certain vectors (e.g. tropical mosquito species).

If the viruses have penetrated an organ, they go through a certain sequence of steps in the cells. The first step is so-called adsorption, attaching to the host cell. Infection can only occur if the virus matches certain surface characteristics of the cell.

This is followed by what is known as penetration, the entry into the interior of the cell. This happens differently depending on the type of virus. Often the virus is swallowed by the cell or transported inside. In other cases the virus and cell merge. The comparison to a Trojan horse is appropriate here. If the entry is successful, the next step is to release the virus genome, known as uncoating. The interior of the Trojan horse can now enter the cell.

With the help of the protein synthesis apparatus of the host cell, what is known as replication can now take place. The virus genome is multiplied, new virus proteins are formed. In a so-called assembly phase, all virus components are assembled. This allows the newly formed virus to leave the host cell again and infect other cells.

Replication of a virus

In addition to the described life cycle of viruses, including adsorption, penetration, uncoating, replication, assembly and release, there are different replication strategies of DNA and RNA viruses as well as differences between lytic and lysogenic cycles. The mechanisms by which viruses exploit their host cells are diverse.

It is important to distinguish between the replication of bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) and eukaryotic viruses (viruses that infect eukaryotic cells). Eukaryotes can be both unicellular and multicellular and include plants, animals, fungi and protozoa.

Once a virus is in a bacterial host cell, there are two routes of replication: First, the lytic cycle, which occurs when DNA damage or other stress factors occur. Here, the bacteriophage takes over the transcription and translation machinery of the host cell. Second, in the lysogenic or temperate cycle, bacteriophage genes are incorporated into the bacterial host genome. The phage genome is then replicated in a benign, dormant state: the phage genome can be expressed when the bacterial cell is stressed (e.g., when nutrient deprived).

All DNA viruses replicate in the nucleus (except poxvirus). While all RNA viruses replicate in the cytoplasm (except influenza and retroviruses).

Viruses and bacteria - what is the difference?

Viruses and bacteria can cause very similar symptoms. However, there are clear differences in structure and composition between the two groups of pathogens. This is important to know because this results in completely different treatments.

Unlike viruses, bacteria are small, single-celled organisms. Therefore, under suitable environmental conditions, bacteria can also multiply outside of another organism - unlike viruses. A key difference between bacteria and humans, animals and plants is that they do not have a cell nucleus.

Not all bacteria make us sick. On the contrary: many strains of bacteria are essential for us humans and an important part of a healthy intestinal and skin flora.

Mutation of viruses

Viruses can change through mutations in their genetic material. If errors occur in the replication phase described above, small genetic changes can occur. In the vast majority of cases, this leads to the virus no longer being able to function. Nevertheless, mutations are helpful for the long-term survival of the virus's offspring. This can lead to variants of the virus that can withstand potentially difficult conditions.

A good example of this is the coronavirus. The omicron mutation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has over 30 mutations in the spike protein alone, 10 of which are in the area that docks onto the body's cells and thus enables penetration into the cell. In total, the omicron virus makes it easier to evade the immune system via immune escape and to reinfect even vaccinated or recovered people.

It is also possible for an organism to be infected by two different virus strains at the same time - for example with the flu virus. In this case, entire gene sections can be exchanged, creating a completely new subtype. This is called antigen shift.

Omicron variant of the coronavirus

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus that has a viral envelope. It is genetically most similar to two other corona viruses that only occur in bats. Therefore, bats are a possible original source of SARS-CoV-2, but there may have been an intermediate host.

The surface feature of the cells to which SARS-CoV-2 can attach itself (adsorption) is the so-called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Attachment occurs via the spike protein of the coronavirus. The many mutations in the spike protein in Omicron are a key reason for the increased transmissibility and the overall low sensitivity to neutralizing antibodies.

Compared to previous variants, Omicron multiplies much faster. However, the risk of becoming seriously ill with a corona infection has decreased significantly with Omicron. This is still possible - especially for risk groups and unvaccinated people.

Other common types of viruses

Viruses have many similarities in their structure, but there are also numerous differences. This mainly concerns the way in which they are transmitted, which organ system they affect and the symptoms they cause.

The following is an overview of some of the most important types of viruses globally. These include the Epstein-Barr virus, the Ebola virus, the human papilloma viruses, the Zika virus, the norovirus, the hantavirus, the hepatitis viruses, the HIV virus (information on the latest developments in HIV vaccination can be found here), influenza viruses and, last but not least, herpes simplex viruses:

Infectious diseases

Transmission routes and preventive measures

In addition to the various transmission routes of viruses, such as droplet infection, smear infection, blood contact and sexual transmission, there are global health threats such as the Zika or West Nile virus, which is transmitted by mosquitoes. In addition, there are newly emerging transmission routes or vectors.

The most effective preventive measures against viral infections include hygiene measures and vaccinations. In addition to the goal of a vaccination, which is to protect the vaccinated person from an infectious disease, it is also about preventing a serious course of the disease and possible subsequent diseases. As the Corona pandemic has shown us, recommendations for certain behaviors, such as social distancing and wearing masks, can also help to protect us.

Symptoms and treatment

As many viral diseases are associated with serious consequences, the question of treatment options arises. A basic distinction is made between therapies that aim to alleviate the symptoms caused and those that target the virus itself, i.e. combat the actual cause.

For most viruses, the only option currently is to treat symptoms if the symptoms are more severe. This applies to most cold viruses, where the symptoms appear quickly but also subside quickly. Medications such as paracetamol can reduce any fever. Stopping the viruses is not yet possible.

In certain cases, there are medications that can be used to specifically combat the virus. These are so-called antivirals. These have a preventive effect. They can prevent the virus from multiplying in the body. However, if this has already happened, the viral disease takes its course.

The preparations target different steps in the life cycle of viruses. Some prevent the virus from attaching to and penetrating the host cell, others prevent the release and reading of the viral genome. Some disrupt the assembly of the virus components and still others prevent the expulsion and release of new viruses from the host cell. The decision as to whether there is a suitable preparation and whether treatment with it makes sense is best made by those affected together with their family doctor.

The contents of this article reflect the current scientific status at the time of publication and were written to the best of our knowledge. Nevertheless, the article does not replace medical advice and diagnosis. If you have any questions, consult your general practitioner.

Originally published on